By Walma Zala, Arts & Culture Correspondent

More than two years after the Taliban’s return to power in August 2021, Afghanistan’s music scene remains stifled under a total ban. Musicians, singers, and music lovers across the country have faced a stark choice: either abandon their profession or flee. While the Taliban’s Ministry of Information and Culture insists that artists and former singers should focus on “religious chants and Islamic anthems,” many say they have lost their livelihoods, public stages, and any sense of artistic freedom. Based on information gathered from multiple sources and interviews with local musicians, this report offers a detailed look into how Afghanistan’s centuries-old musical heritage is facing unprecedented threats under Taliban rule.

Taliban’s Position on Music

From the outset of their second takeover, the Taliban labeled music as “haram” (religiously forbidden) and systematically moved to confiscate or destroy musical instruments. All major forms of music have been prohibited, including public concerts, radio or TV broadcasts featuring songs, and private wedding performances. As a result, thousands of musicians and singers have abruptly lost their income streams and professional identity.

A spokesperson from the Taliban’s Ministry of Information and Culture explains the regime’s perspective:

“We encourage those who call themselves ‘artists’ to dedicate their talents to Islamic chants, religious poetry, and nasheeds that do not conflict with Afghan culture and Islamic law.”

Yet, musicians and singers say that these limited opportunities—primarily involving Islamic nasheeds—do not come close to substituting their original craft.

Proposed “Alternative” Work for Artists

The Taliban have repeatedly stated that ex-singers and music producers could repurpose their skills to produce nasheeds and other forms of religious content. According to officials, the goal is to align musical talent with what they define as “authentic Afghan culture” under Islamic rule.

However, it remains unclear how many musicians have actually been able to transition into such work. Most former singers describe the Taliban’s view of them as profoundly negative, underscoring a climate of fear and deterrence rather than real collaboration.

Life in Hiding or Forced Migration

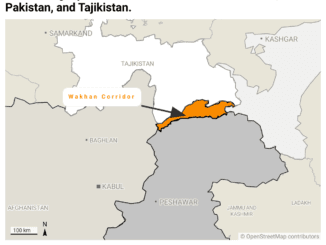

With the new restrictions, scores of Afghan singers and musicians have fled the country—some to neighboring Iran or Pakistan, others to Central Asia or Europe. Those unable to leave remain inside Afghanistan, mostly in hiding or surviving on menial, non-musical jobs to feed their families.

Mehri (Mir Muftoon), 61, a renowned local singer admired for his unique style, chose to stay in Afghanistan and has all but abandoned his craft. He now lives in a village in Badakhshan Province:

“We follow the law of the land. Since music is not allowed, we don’t play it. I spend my time farming, even though we have our own farmers. Sometimes, I go to Tajikistan for a month, and if I long for music, I return.”

For most musicians, even a short international trip to express their artistic vision is not an option. They are effectively unemployed or forced to do low-paid work—anything from driving a taxi to selling groceries—to survive.

“From Wedding Stage to Driving a Taxi”

A Pashto singer still living in Afghanistan, who asked to remain anonymous, says many famous musicians are now struggling to make ends meet:

“Many singers drive cars in the city or even sell rice on the streets. Some are working as day laborers. Their fame is gone, and so is their income.”

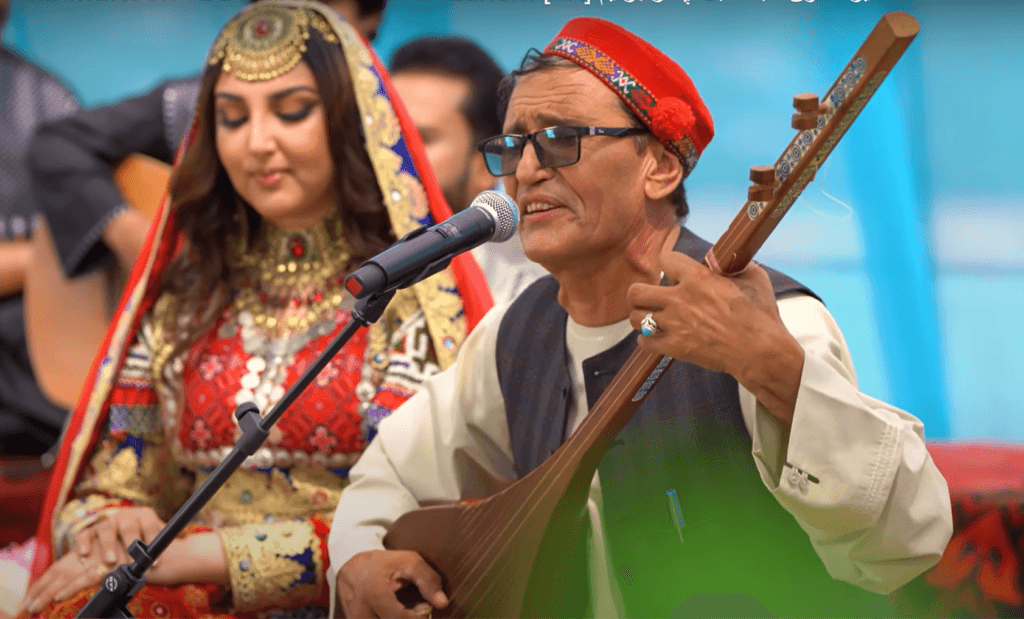

Events that once supported local artists—including wedding parties, holiday gatherings, and private family celebrations—have reached a virtual standstill. Gone are the days when performers would bring cheer to social occasions with the beats of their Tablas or the strumming of their Rubabs.

From Music Stars to Day Laborers

One example is Habibullah Shabab, a youthful artist formerly renowned in Helmand and Kandahar provinces for his local folk tunes. With the Taliban’s ban in place, Shabab lost his livelihood. He opened a small food store in his village to survive, but it soon failed, and he now scrambles for day-labor jobs:

“I used to enliven weddings and festivals with my performances. But after the Taliban’s return, there is no work for musicians like me. Many have gone to Iran or Pakistan, but I stayed because of my love for my homeland. Yet here I am, jobless, struggling to feed my 12-member family.”

Shabab pleads with the Taliban administration—and wealthy Afghans—to offer jobs to artists who, in his words, “have higher education and can still serve the country in different capacities.”

Fleeing Abroad: Searching for Safety and Musical Freedom

Due to easier border crossings, many Afghan musicians initially fled to neighboring countries, particularly Iran and Pakistan. However, opportunities for artistic expression there are also limited, and many live in constant fear of deportation.

Naseer Parwani, a Dari-language singer with 30 years of experience, escaped Afghanistan when the Taliban seized Kabul. On the night the Taliban entered the city, he and fellow musicians burned their instruments to avoid punishment. Today, Parwani works in a small shop in Iran, and his son—once a jazz drummer—has had to take up tailoring:

“We came to Iran out of desperation. Without music, we must do any job that puts food on the table. We have visited the UN offices several times, but no one pays attention to our plight.”

Estimates suggest that around 500 Afghan singers and artists are taking refuge in Iran. Many are in dire straits, lacking official documentation and often facing threats of arrest and deportation.

The Story of the “Bakhsh” Brothers

Another example is Naazim and Nazeem Bakhsh, part of a renowned musical dynasty going back generations in Kabul’s fabled “Kharabat” neighborhood, a cradle of Afghan music. Their father, Nadim Bakhsh, and grandfather, Ustad Rahim Bakhsh, were both celebrated artists. Naazim, 24, used to play the tabla while his brother performed vocals:

“Before, we were always booked—we hardly spent a night at home because of performances. After the Taliban returned, we tried to hold on, but it became impossible. They closed Kharabat, and we had no choice but to leave the country.”

The siblings now live in Pakistan without legal status, fearing arrest or forced deportation:

“We get one or two shows a month if we’re lucky. The rest of the time, we are jobless and worried.”

In the West: Mixed Fortunes for Exiled Musicians

Some Afghan musicians have successfully resettled in Western countries, where they have begun rebuilding their musical careers. Although they enjoy greater freedom to produce and perform, they face logistical hurdles, such as securing instruments, studio space, and financial support. Many lack family networks or substantial resources, compelling them to juggle menial jobs alongside music.

“A Silent Land”: Risks of Cultural Erasure

Dr. Ahmad Naser Sarmast, head of the Afghanistan National Institute of Music, now exiles from Portugal. He argues that Afghanistan is on track to become the only country in the world effectively “muted” by legal decree against music. Dr. Sarmast warns that if Taliban policies remain unchanged:

“We could lose a musical tradition and a significant part of our cultural and ethnic identity. Taliban rule will leave Afghanistan culturally impoverished and psychologically afflicted.”

He believes it is crucial for religious scholars with proper theological grounding to speak up, clarifying there is no direct Quranic prohibition of music. Without a shift in attitudes, Afghanistan’s once-vibrant musical heritage may fade within a generation.

What Lies Ahead?

Under the Taliban, concerts, media broadcasts of music, and even private events remain illegal. Many musicians hide instruments or play in secret gatherings far from the public eye. Those who remain in the country are often desperate for alternative work, while those who have fled fight for survival and legality abroad.

Despite these challenges, some exiled Afghan musicians have begun producing new music outside the country. However, according to Dr. Sarmast, “Without fundamental changes in Afghanistan’s internal policies, the country’s musical renaissance will only happen in the diaspora.”

Habibullah Shabab and others who have chosen to stay hope that the Taliban administration—or the Afghan populace at large—will realize the cultural and economic value of music. The future of Afghanistan’s rich musical tradition hangs in the balance, with a generation of artists waiting in uncertainty.

In the aftermath of the Taliban’s sweeping music ban, Afghanistan’s once-thriving music industry teeters on the brink of collapse. Musicians who brought joy to weddings and celebrations have become farmers, shopkeepers, or taxi drivers—if they have managed to find work. Others live in exile, scattering to nearby countries or trying their luck in the West.

What remains unshaken is their deep desire to protect and nurture Afghanistan’s musical identity. Whether through whispered performances behind closed doors or nasheeds transformed into subtle expressions of cultural pride, Afghan artists continue to demonstrate resilience. Yet, without structural changes in Taliban policies or meaningful intervention by the international community, the fate of Afghan music—and the livelihoods of its proud creators—will remain perilously uncertain.

About Yaraan Web

Yaraan Web is a leading platform highlighting stories of culture, society, and human rights in Afghanistan and beyond. Through in-depth reports and human-interest features, we aim to illuminate Afghan communities’ resilience and challenges.

Be the first to comment